Tesla Moves on from the Model S and Model X

Cars aren’t the center of Tesla’s story now

On Tesla’s January 28 investor call, CEO Elon Musk said Tesla will discontinue both the Model S and the Model X. “It’s time to basically bring the Model S and X programs to an end with an honorable discharge,” he said. “If you’re interested in buying a Model S and X, now would be the time to order.”

These models dropped in deliveries—and in relevance—as the Model 3/Y scaled and as competitors brought compelling alternatives to market. S/X deliveries peaked at 101,312 in 2017 (the first year Model 3 was on sale); Tesla’s “Other Models” deliveries were 50,850 in 2025—a bucket that bundles S/X with Cybertruck. Tesla delivered 1,585,279 Model 3 and Model Y vehicles in 2025.

Replacements were not mentioned and shouldn’t be expected: Musk said, “We’re going to take the Model S production space in our Fremont factory and convert that into an Optimus factory.” Tesla’s broader messaging emphasized AI, robotics (Optimus), autonomy, and energy at mass scale as a means to long-term societal transformation.

All this is more reinforcement that Tesla’s focus is autonomy, and cars are increasingly a means to that strategic end. For Tesla, selling cars funds and provides the underpinnings to scaling autonomy and robotics.

Where does this leave Tesla in the automative space?

The Master Plan

In automaker terms, Tesla is exiting the flagship sedan and SUV premium segments. It’s fair to debate whether this was the plan all along or whether Tesla lost the plot on the S/X.

At least as far back as 2016’s Master Plan, Part Deux, though, Tesla made clear its focus on covering “the major forms of terrestrial transport,” which included the Model 3, a compact SUV (which became the Model Y), and “a new kind of pickup truck” (today’s Cybertruck). It framed premium sedans and SUVs as “relatively small segments.”

Part Deux also introduced development of “self-driving capability that is 10x safer than manual via massive fleet learning,” and the idea of customers being able to add their personal cars to what Tesla now calls its robotaxi fleet.

These ideas from 2016 evolved into key components of its expanded strategy.

Non-Competition

In line with its broader plans, Tesla is behaving increasingly unlike a traditional automotive competitor. It’s not expanding into segments—instead narrowing to high volume—and it’s not broadening its car brand portfolio.

Tesla’s 2025 Proxy Statement ties executive incentives to an operational milestone of 20 million Tesla vehicles delivered cumulatively within a defined 10-year performance period (page 67). The Letter to Shareholders in the Proxy also notes Tesla has already delivered its 8 millionth vehicle, which implies roughly 12 million additional deliveries to reach that milestone—meaningful, but not the kind of unit-growth plan that, by itself, signals a segment-by-segment offensive against major automakers.

Instead, Tesla’s role in the automotive industry is to push autonomy forward aggressively. It appears poised to keep the Model 3, Model Y, and Cybertruck competitive to generate the sales volume it needs—both to fund priority products and to maintain a large enough fleet for training. But it won’t compete category by category. Vehicle sales won’t be the primary measure of success.

That Elon Musk has openly admitted Tesla’s talked to other automakers about licensing Full Self-Driving (FSD) is worth revisiting in this context. So far the automakers have declined. If Tesla is decreasingly a direct competitor—and has a leading automated-driving offering—does it become strategically sound to partner?

Tesla’s Self-Driving Bet

A core Tesla bet is it will lead in autonomous driving. Given the scale and impact Tesla is expecting, its vehicle sales goal relative to the size of the larger automotive industry, and Musk’s expressed openness to working with others, the implication is Tesla will power vehicles beyond its own.

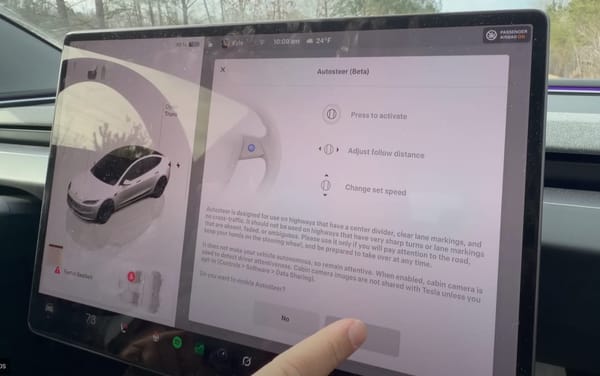

Tesla has a large installed base by any current ADAS standard. In its FY 2025 earnings, Tesla shared it had 1.1 million FSD U.S. subscribers (page 7) at the end of 2025. That represents steady growth from 400,000 in 2021 (page 7). Reuters says Musk expects Europe and China to approve FSD soon.

FSD reviews are improving, but still mixed. The common critique is FSD highly impressive at points but inconsistent—a suboptimal combination, given it can invite over-trust but make enough mistakes that vigilance is needed.

Still, Tesla FSD recently won Motor Trend’s Best Tech Driver Assistance award; the publication says “there is no system more advanced” and that the version they tested (v14) is “vastly improved” compared to the previous version they tested (v12). Tesla FSD was recently used in two different cross-country tests with supposedly zero intervention (a “Tesla FSD Cannonball Run” from Los Angeles to New York City and a trip from Los Angeles to Myrtle Beach ).

So, the product has encouraging early adoption and is getting better at a respectable clip. Waymo’s self-driving, though, is ahead of Tesla’s—Waymo is at Level 4 while Tesla is at Level 2. How does Tesla think it will win?

A quick reference on driving automation levels:

- Level 1—Driver Assistance: The system provides continuous help with either steering or acceleration/braking; the driver does the rest and monitors the environment.

- Level 2—Partial Driving Automation: The system provides continuous steering and acceleration/braking; the driver still monitors the environment and must be ready to intervene immediately.

- Level 3—Conditional Driving Automation: The system performs the entire dynamic driving task within a specific operating envelope defining where it works (which roads), when it works (weather and lighting conditions), and how it’s expected to operate (speed and traffic complexity). The driver becomes a fallback-ready user who must take over when the system requests.

- Level 4—High Driving Automation: The system performs the entire driving task and fallback within its operating envelope; no driver is required while operating in that operating envelope.

- Level 5—Full Driving Automation: The system performs the entire driving task and fallback under all roadway and environmental conditions (there is no operating envelope limitation).

Waymo provides Level 4 self-driving today in a constrained operating envelope. Its technology stack is a geofenced, map-driven, multi-sensor autonomy system fusing cameras, LiDAR, radar, and other sensors, high-definition maps, and in-vehicle AI. Waymo’s fleet is backed by a substantial operational layer consisting of fleet operations and remote assistance and monitoring.

Tesla’s current FSD is Level 2. Its technical approach is a camera-centric hardware system with robust in-car compute and heavy reliance on AI and its massive fleet of vehicles for training.

The aspirational endpoint for Tesla, Waymo, and all others is Level 5: autonomy anywhere, without an operating envelope that constrains location, condition, or speed and complexity.

Ben Thompson of Stratechery provided a take on why Tesla thinks its approach will win in the article Elon Dreams and Bitter Lessons:

The Tesla bet, though, is that Waymo’s approach ultimately doesn’t scale and isn’t generalizable to true Level 5, while starting with the dream — true autonomy — leads Tesla down a better path of relying on nothing but AI, fueled by data and fine-tuning that you can only do if you already have millions of cars on the road.

Thompson bases this on core points from Rich Sutton’s 2019 article The Bitter Lesson. The implications to autonomy are that Tesla’s large-scale learning approach (AI leveraging data from Tesla’s huge fleet) will beat Waymo’s more bounded approach which uses AI in a narrower way and layers it with a sensor- and map-heavy hardware stack (more cameras, LiDAR, radar, etc.).

Sutton:

Seeking an improvement that makes a difference in the shorter term, researchers seek to leverage their human knowledge of the domain, but the only thing that matters in the long run is the leveraging of computation.

“Human knowledge” in this context is Waymo’s leveraging of maps, geofencing, and specialized sensors that speed near-term success (explaining why Waymo is at Level 4 while Tesla is at Level 2). The Bitter Lesson would predict Waymo’s elements could become a scaling bottleneck relative to Tesla’s enormous fleet data and iteration velocity (through software distribution and training loops).

Sutton makes another point that might explain how Tesla would be able to leverage this eventual scaling lead:

These two need not run counter to each other, but in practice they tend to. Time spent on one is time not spent on the other. There are psychological commitments to investment in one approach or the other.

The implication here is for automakers and suppliers, who would be left in an uncompetitive position if they follow a Waymo-like approach without appropriate hedging. The Bitter Lesson dynamic would imply (and Tesla seems to be betting) other parties would be highly motivated to license FSD.

This is an attempt to understand the reasoning behind Tesla’s decisions and strategy, not a prediction who will win or lose. Musk has been making ambitious FSD promises since 2016, so skepticism is warranted. Technology dynamics are only one factor, and the rate of change, particularly in AI, could shift things significantly and quickly. The market and regulators could also favor approaches that are measurably safe sooner, which in the nearer term would strongly favor approaches like Waymo’s.

Tesla and the Car Market

Tesla seems set to keep the Model 3, Model Y, and Cybertruck competitive for the foreseeable future. Beyond that baseline, the company’s center of gravity is autonomy and robotics.

For buyers, the decision stays the same: judge the product on its merits. Just remember that Tesla’s priorities aren’t always aligned with those of its current customers.

For the auto industry, this means less treating Tesla as a segment-by-segment car rival and more as a potential platform player—one that could influence how automated driving features are built, sold, and eventually licensed.