Cars Are Still Cars. They’re Also Computers.

The promise of software-defined cars is real. So are their pitfalls.

Software is magic.

The world is filled with intricate, increasingly miniaturized, energy-efficient systems—smartphones and watches, AI glasses, wireless earbuds—all engineering marvels. What brings them to life, though, is software—transforming them into cameras, scanners, remote controls, compasses, navigators, translators, ride dispatchers that send drivers to you, and butlers that turn on your lights when you pull in the driveway.

This sounds obvious by now—almost 20 years beyond the introduction of smartphones and apps, over 30 years past the internet explosion, and 40-plus years after the rise of the PC—but you feel that tingle again when software makes its way into an object or machine you spend a lot of time with. You can feel it in cars today.

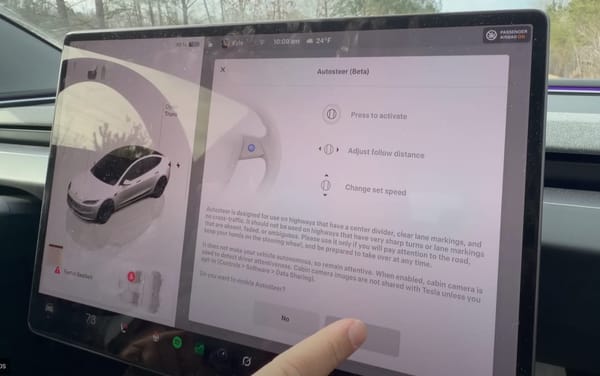

We’re getting a partial flavor of what software can do in newer models, through features like advanced navigation, hands-free driving assist, and advanced parking assistance. There are moments of greatness mixed with confusion and disappointment. Software in cars is in its adolescence—brilliant one day, baffling the next.

We are all navigating a transition, consciously or not, from cars as we’ve known them to what the automotive industry is calling “Software-Defined Vehicles.” The change started slowly, in a few areas like audio and navigation (now grouped under “infotainment”), over a decade ago, and is now accelerating and expanding across the car. Electrification isn’t the same as software-defined, but the two are often arriving together—in part because modern EV platforms are typically more compute-centric, better connected, and easier to update.

Technologists and product folks relish a time period like this, filled with innovation potential, while everyone else is just trying to figure out what works for them as they go about their lives. My neighbor recently bought a new BMW X7, and I asked him what he thought of it: “Too much tech,” he said without elaborating. Most people don’t want what feels like tech for tech’s sake; they want a benefit they can understand and trust, that does what they expect in a way they expect. Car tech isn’t yet delivering this consistently.

Tesla drivers have experienced the most software growing pains. Tesla’s aggressive approach means we’ve seen the extremes, both the best of what’s to come (meaningful feature additions after purchase, user interface enhancements, route planning and range improvements) and the worst (controls on the screen can change without warning, quality regressions). Newer entrants like Lucid and Rivian are also software-forward, though both are more measured in how updates are delivered.

Outside a handful of leaders, most automakers are still early in the journey. When over-the-air (OTA) software updating is being promoted as a novel feature, and many cars still can’t do it (or it doesn’t work well), it’s a sign of early days.

The industry term “Software-Defined Vehicle” (SDV) is another giveaway we’re at the beginning. The buzzword will fade away, but the underlying promise—software at the core, controlling and enabling everything—is shaping what we’re experiencing today and what’s envisioned for tomorrow.

At many levels, we’re still just imagining what we’ll be able to do. Cars are increasingly filled with screens, microprocessors, microphones, sensors, and connectivity. Software will let you enable nearly anything with them—shaping not just what the car displays, but how it behaves. It feels like the opportunities are limitless, but dreaming big in cars is uniquely challenging:

- Software bugs on phones and computers are annoying. In cars, they can have life-or-death consequences.

- Screens are plenty big enough for video calls. Shouldn’t you be looking at the road?

- Over-the-air (behind the scenes) software updates are great! How do you feel about your car working differently today than it did yesterday? What happens if you notice the change at the wrong moment—like while you’re on a busy highway?

- It’s freezing cold, but luckily the salesperson said your new car is “heated-seat capable.” How do you feel when you push the button and you’re prompted to subscribe? (And did you add your credit card to the car?)

We’ve been hearing about full self-driving for a while. Why can’t cars fully drive themselves yet? To get a sense, take a drive through a major city to experience a slice of the infinite scenarios a self-driving car has to understand. Trucks stop and block the street, buses merge with little or no warning, pedestrians move in and around the road (some of them signaling)—there are countless edge cases and moments of human unpredictability. Humans handle this mess with context, negotiation, and intuition. Teaching a machine to do the same—safely, everywhere, every time—is hard.

There is real momentum today. Much more is coming, step by step: limited self-driving (moving towards higher levels of automated driving at an increasing pace), broader hands-free assist, those over-the-air software updates, digital keys and cloud profiles, post-purchase feature upgrades (many with a subscription cost attached), self-diagnosis capability that schedules service automatically. Software will drive all of these. And it will bring to life countless features and experiences we can’t imagine yet, but once we experience them, we won’t know how we ever lived without them.

There’s also a broader implication: software doesn’t just change the car—it changes what it means to be a carmaker. As vehicles become more modular and platform-driven, the boundary of who can build a credible vehicle is shifting. Xiaomi is one signal: an electronics-native company that brought an EV to market (the SU7) on modern EV platforms on a timeline that would’ve been unthinkable until recently—especially for a firm that didn’t start in the car business. This is already expanding the field of competitors. Legacy automakers will have to respond by pairing their strengths in scale, safety, and service with faster software iteration in areas like advanced driver assistance (ADAS), user experience (UX), and energy management. For consumers, it means more of the types of changes outlined above—arriving sooner and across more brands.

Behind the scenes, automakers are working to bring order to the burst of activity that these opportunities—and unknowns—have unleashed. Most are trying out different features and experiences, some more aggressively than others. In parallel, they’re sorting out their systems and software platforms, which is a prerequisite to fully delivering on the promise. They’re also trying to anticipate shifting regulatory frameworks and expectations across safety, cybersecurity, privacy, and driver-assistance. The changes are also reshaping the industry’s ecosystem—shifting leverage toward platform, silicon, cloud, mapping, and cybersecurity players, while forcing traditional suppliers to reposition.

This kinetic and innovative period, with its promise and pitfalls, is what inspires Road & Reason. I’ve been a car enthusiast longer than I’ve been anything else, and I’ve built a career in technology. The intersection of cars and technology is not new, but we’ve reached a point where technology’s role is moving from one of incremental conveniences to a tectonic force that will, over time, reshape nearly everything about the modern vehicle as we’ve known it. My goal with Road & Reason is to make sense of where cars are going—and why.

It’s going to be quite a ride.